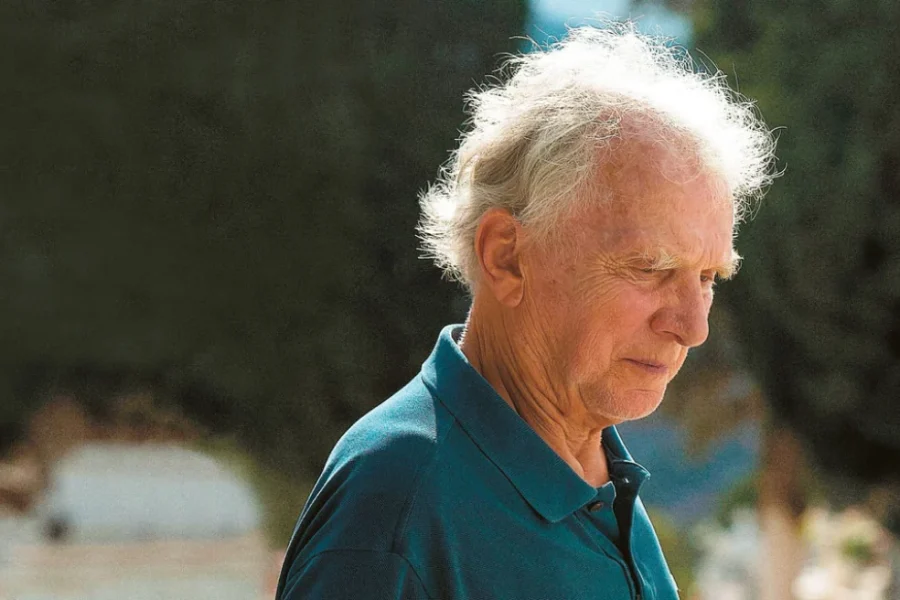

Now 80 years old, Swiss dentist Julien Grivel is the subject of the documentary Carved Souls by acclaimed director Stavros Psillakis. For 26 years, Grivel cared for patients suffering from Hansen’s disease (commonly known as leprosy), many of whom had been relocated from the infamous leper colony of Spinalonga to the “Agia Varvara” Infectious Diseases Hospital in Aigaleo, Attica. His work was entirely voluntary.

In the film, a patient says to Grivel: “Through such trials, the soul of a person becomes beautifully sculpted.” This sentiment encapsulates the heart of Grivel’s story—a man who, over decades of selfless service, became not just a caregiver, but a friend, student, and local hero to those he treated.

Most of his patients were from Crete, particularly Spinalonga, and they welcomed him not only into their lives but into their culture. They taught him about the disease, helped him integrate into the community, and ultimately inspired his transformation into a genuine Philhellene—a deep admirer of Greek culture and values.

One such person inspired by Grivel’s story was director Stavros Psillakis, who, after reading the doctor’s memoir detailing his years in Greece, decided to bring the full story to the screen. Filmed partly in Cretan villages and hospital wards, Carved Souls offers a message of hope, solidarity, and human dignity in the face of adversity. The film received three awards following its premiere.

A Moving Premiere

The film premiered at the packed Olympion cinema in Thessaloniki, attended by both Psillakis and the 80-year-old Grivel himself, who addressed the audience in fluent Greek. His warm words and heartfelt message captivated the crowd, earning him a long standing ovation.

Two years after receiving the prestigious Golden Alexander Honorary Award, Psillakis returned to Thessaloniki, once again drawing attention with his human-centered storytelling. In his speech, he reminded the audience that art is, above all, a call to “remain upright, facing upward”—a play on the Greek etymology of the word “anthropos” (human).

Grivel, in turn, offered insight into his life’s journey: “When pain and prejudice disappeared, two worlds could meet and flourish. Thanks to acceptance, solidarity, respect, and love, everything became possible. I feel truly enriched by this journey in Greece—by what I gave and even more by what I received.”

Why He Came to Greece

What led a Swiss dentist to leave a comfortable life behind and work—often without any protective equipment—with patients stigmatized and feared by society?

“He encountered the world of ‘difference,’” Psillakis said. “Yes, he could have remained safe and secure in Switzerland. But life is movement. And the daily contact with these people—who lived face-to-face with death—was a lesson in humanity.”

Despite the risk, the film doesn’t dwell on tragedy. Instead, it radiates positivity and conveys what it truly means to be human. Through excerpts from his personal diary, Grivel narrates how his friendship with patients like Manolis Foundoulakis and Epameinondas Remountakis, both emblematic figures of the Spinalonga community, changed his life.

“My Own Ithaca”

Drawing on his diaries, Grivel wrote a book chronicling his journey from the early days with the patients of Spinalonga—many of whom had by then moved to the Agia Varvara hospital—to his deep immersion into Cretan culture. He came to Greece at least twice a year between 1972 and 1998, always volunteering his dental services for free.

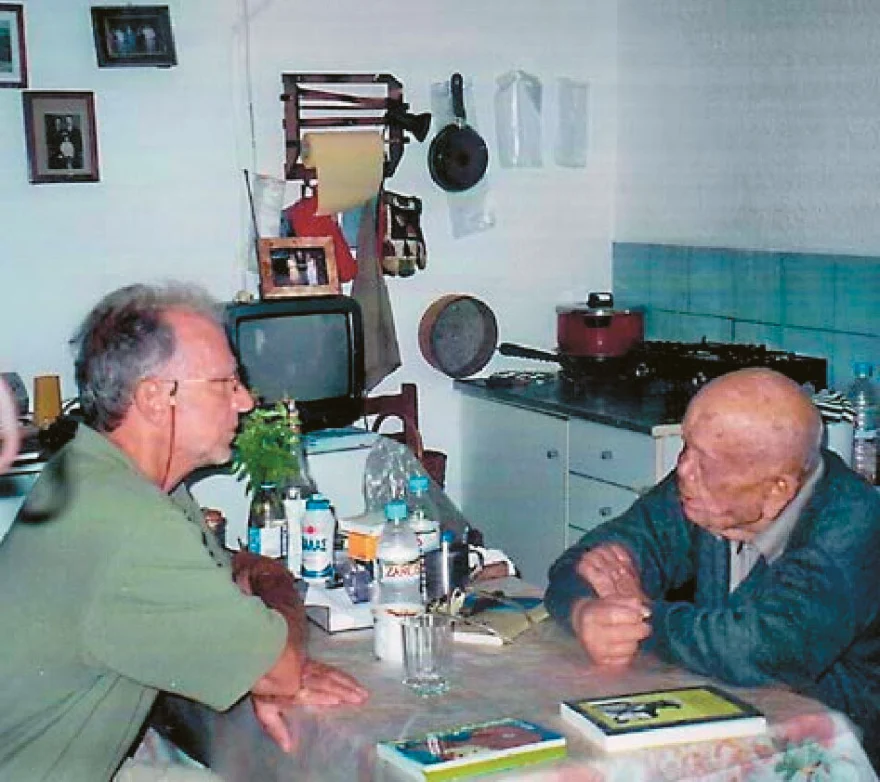

In the film, we see touching scenes of Manolis Foundoulakis—affectionately called “Barba-Manolis” by Grivel—recounting his life story, from his time in isolation on Spinalonga to his reflections on the spiritual lessons gained through hardship. Their relationship evolved into a long-standing friendship, which Grivel describes as one of the most meaningful in his life.

Using archival footage collected by Theodoros Papadoulakis during the filming of the popular TV series The Island, Psillakis weaves a narrative not just of disease, but of profound humanity. “With these people,” Grivel says, “I experienced moments of eternity—deep, essential moments.”

Grivel’s reflections are deeply moving: “I met disabled young people without a single wrinkle on their faces who had achieved incredible wisdom. Their lives were torn apart by a brutal fate, yet they remained upright.” One of his patients once told him: “You forget that you have nothing. Like us, you’re simply a tenant of life.”

A True Philhellene

Psillakis’ film shines a light on the spiritual and existential depth of a man who defied convention to look into the very soul of others. The goal is not just to highlight the social exclusion of leprosy patients, but to offer a message of hope and compassion—embodied in a man whose love for Greece runs deep.

Grivel is the very definition of a Philhellene. He has studied Greek philosophy extensively, from Plato and Aristotle to Epicurus, understands the symbolic power of mythology, and believes that Greek poetry makes us better people. In the introduction to his book, echoing poet George Seferis, he writes: “This land may have little water, but its source of light is inexhaustible.”

His connection to Greece, he explains, is not just historical or emotional—it’s intellectual: “This country gives meaning and depth to my life.”

His relationship with Crete in particular is profound. He embraced the island’s worldview, learned the language, respected its cuisine and raki, and was often seen speaking on behalf of the Cretans as one of their own. The local community accepted him as such.

Honored by Greece

Grivel’s humanitarian work did not go unnoticed. The Academy of Athens honored him with a prestigious award, accompanied by a speech that has since become legendary. Quoting Epicurean philosophers, he said: “In giving, we enrich ourselves.” He reminded us that “Life is a loan, a magnificent gift that does not belong to us. It must be spent with respect and wisdom, lest it run out too soon.”

He never saw his service as charity, but as an expression of necessary altruism and mutual respect. His greatest reward? The genuine affection and resilience shown by people like Manolis Foundoulakis, who passed away in 2010. “That,” said Grivel, “was the real reward: the sincere, unpretentious love and gratitude, the extraordinary lessons of endurance in the harshest of circumstances, the deeply personal confessions that brought peace and comfort, and the wide, beautiful smiles—behind which lay not only pain, but also hope.”

“These kinds of experiences,” he concluded, “cannot be measured in economic terms.”

This is the core message of Carved Souls, a film and a legacy that left everyone who exited the Olympion cinema feeling their souls, too, had been sculpted.

As Psillakis noted, the film ultimately traces the sculpting of the doctor’s soul through his connection with others. No wonder it won the FIPRESCI International Critics’ Award for Best Greek Feature Documentary, the ERT Public Broadcasting Award, and the Youth Jury Award—perhaps the toughest of all, as young viewers are often the most honest and discerning critics.

Source: protothema.gr